- Home

- Jennifer Anne Moses

Tales From My Closet Page 2

Tales From My Closet Read online

Page 2

It was the worst day of my life. The. Worst. Day. And trust me, I’ve had plenty of worst days, not to mention plenty of practice being new.

This is how it went:

First period I had English. Everything was going okay until the teacher gave us an in-class assignment to write three paragraphs about any book we’d recently read. “Pen to paper, students,” she said as kids started groaning. “Pen to paper!”

“Hey, what about I use some of this paper right here?” some genius said, poking me in the back with — I guess it was his finger, since my dress didn’t tear.

“Get over it,” the teacher continued. “Because in this class we’re going to have a daily practice of putting your thoughts down on paper.”

“That’s exactly what I said!” the same finger-jutting joker said, this time patting me a little on the back like I was a pony. I turned around. He wasn’t even looking at me, but rather, beaming to the laughter of the class. He had a huge nose and glasses and skin so pale that it looked see-through, but he didn’t seem to know he was anything but the world’s funniest kid.

So. Not. Funny.

Second period I had chemistry, only because I was the only new kid in class, no one chose me to be their chemistry partner, something that I observed from behind as all the popular kids (you could tell by the way they high-fived each other) partnered up. I had to sit there feeling stupid while the teacher assigned me a chemistry partner: John, who was the only other kid left unclaimed after the partner-picking session was over. Wonder why. Maybe it was the eyeliner he was wearing? Or his green-and-pink-striped hair? Or his neofascist T-shirt? Or his tattoos? Or perhaps merely the way he was sitting, just behind me, hunched up over a notebook, by turns scribbling furiously and flicking his pen back and forth like a drumstick. I tried not to hold his hyper-funk-nihilist-grunge-gender-blended-macho look against him, but it didn’t help when, preliminaries over, I had to get up to sit next to him at the table he’d already claimed in the far left corner of the room, and he leaned in to say: “Where are you from, anyway — Planet Toilet Paper?”

I tried not to take it personally — after all, he was a guy, as was the finger-jutting jerk from English. Because, and not to put too fine a point on it, as far as I was concerned, in general guys, while occasionally cute, were basically several layers of evolution behind girls. My mom kept telling me that eventually they catch up, but so far I’d seen little evidence of it. “Your father was a teenage boy once upon a time, too,” she’d say, which didn’t exactly boost her argument.

Just when I was figuring that things had to improve, along comes third period — American History — and, just my luck, there was Becka, sitting next to another extremely pretty girl. Both girls sat with their right legs crossed over their lefts, and as I glanced their way I could see Becka give the other girl one of those subtle, fleeting lip curls that can only mean one thing: They’ve already been talking about you. Everything about Becka — from her new, simple white button-down blouse, to her perfect pencil skirt, to her toenails, painted a perfect, soft pink, and her sandals, which were flat and excellent, with silver straps — said that she was better, more expensive, and classier than other girls, that she was special, a cut above, headed for the heights. Around her neck hung that same delicate pink-and-gray scarf that she’d been wearing when I met her, which she fingered on and off as if it were a talisman. Becka’s sidekick was more interesting, or at least she was in terms of sartorial sensibility. First off, her long brown hair was plaited into two perfect braids, so long and silky they were like tassels, and as for her outfit, which was so fabulous I glowed with envy, especially as I knew that, with my shape, I’d never be able to pull something like it off, it was:

On top, a silky blouse with lace, like a nightie.

On bottom, cutoff jeans with fraying ends that came to just above her knees.

On her feet, bright-pink All Star high-tops.

Actually, the more I looked, the more I realized that Sidekick’s nightgown-style blouse was in fact a very short nightie, which was something that even Eliza, the queen of creative castoffs, had never tried. But, unlike Eliza, Becka and her PJ-wearing pal were both the kind of high school beauties, tall and elegant as swans, who intimidated grown-ups, so much so that every time the teacher happened to direct his attention toward them, he stretched his neck away from his collar, like he was choking.

Watching him was painful. But otherwise he seemed to know what he was talking about, and the class passed quickly, with nary a snarly comment thrown my way. And then Becka happened. All over again. Lucky me.

“Hey, Um! This is Robin,” she said as I was making my way toward the door at the end of class. Then, turning to Sidekick/Robin, she said: “Um just moved in across the street.”

“Nice to meet you,” the girl said, clearly not meaning it.

“I’m Justine,” I said.

“Can I ask you something?” Sidekick said.

“Sure.”

“What are you wearing?”

I looked down. “A paper dress. It’s an original.”

“I think it got leaked on,” she said.

I looked down to inspect but didn’t see anything.

“In back,” she said. “Like, all over. Unless it’s part of the design?”

“Um’s from San Francisco,” Becka said. “She’s very original.”

“I still don’t see it,” I said.

“It’s all the way in back,” Sidekick said, “just below your shoulders.”

“Maybe you can cover it up with paper towels?” Becka said. “No one would even notice.”

Which is when I felt my face go on fire, and worse, began to sweat, soaking my astonishing dress in blobs of dark stain.

This was so not working out the way I had envisioned it.

So.

Not.

Lunch was next, so I had time to run into the girls’ room, where, craning my neck around, I saw it: splattered from my shoulder to my waistline were blobs of blue ink. It was then that I remembered my chemistry partner flicking his pen back and forth while I sat in front of him, at the next-to-closer-to-the-blackboard table, before the teacher put us together as lab partners. He probably did it on purpose, the jerk. I tried to blot it out, but it only made things worse. Now I really did look like I was wearing a giant piece of toilet paper.

I was so upset I nearly cried, but didn’t. For one thing, I don’t cry. For another, there was another girl in the bathroom. Because it’s bad enough to cry, but to cry in front of a total stranger, on the first day of school, in the girls’ room? NEVER. Plus, I recognized her from chemistry class. She was one of the girls in the front row and had instantly gotten teamed up with some big jock with the kind of all-American looks that belong on cereal boxes.

“Hey,” the girl said as she bent to wash her hands in the sink next to mine.

“Hey.”

“Cool dress,” she said.

“It’s paper.”

“It is?”

She herself was wearing shorts and a loose top with sandals. She had straight brown shoulder-length hair, muscular arms, and a figure like a hip-hop star — not thin but not fat, either, which, with her height, she totally pulled off. Also, she had a set of perfect big white teeth, and she was smiling at me with them like she was in a toothpaste commercial. In short, this was a girl who knew she was pretty and always had. She was probably dating the captain of the football team. She was probably best friends forever with Becka and Robin, and was already planning on telling them about the new girl with the paper dress.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen a paper dress before,” she said, still smiling, but smiling like she didn’t mean it, in a way that let me know she thought I was a loser.

“Well,” I said, “later.” Because, as I exited the girls’ room and emerged back into the chaos of the hallways, two things were obvious: first, that Toothpaste Smile girl thought I was a freak, and second, that I’d landed in an entirely different

fashion universe from the one I’d come from in San Francisco.

One thing I knew for sure was that if even one more kid said something nasty about my dress I’d be in actual danger of actually crying. Already I could feel the hot burn of tears behind my eyeballs, but I pushed them back with this kind of cranial-sucking-in movement I’ve perfected, and went looking for a place I could sit where I wouldn’t be totally alone or, even worse, unwanted and out of place at some table reserved for this or that clique.

For the first time that day, I was in luck. At a table with a total geek (complete with the too-big tortoiseshell glasses and the sticking-up hair); a couple of vaguely bored-looking girls peering suspiciously at the contents of their lunch bags; a chubby, very pale girl talking with her hands; a girl done up in the classic low-key tomboy uniform of jeans and T-shirt with the classic sassy short hair style, whose one sign of fashion flair was the thin gold bangles she wore on her right arm; and another girl in pure pale-blue prep, there was an open spot at the very end, a seat-gap’s length from anyone else. If this wasn’t a nonclaimed table, nothing was.

“Hi,” I said, sitting down and making a little space for myself with my tray, which I hoped would show that I wasn’t trying to elbow in on anyone’s lunch routine.

“You new?” Tomboy Girl asked me.

“Just moved here.”

“Yeah? Where from?” This time she smiled, lips curling up like she was actually interested.

“San Francisco.”

“Must be nice in San Francisco.”

“Yup.”

“I’m Ann,” she said, flashing a grin, which instantly revealed killer cheekbones and dimples. She was built tiny, like a ballerina, and her beautiful skin was the beautiful color of oak. As she reached for her milk, the bangles on her arm made a tinkling sound. I don’t know why, but I liked her at once.

“I’m Justine,” I said, picking up half of my sandwich.

“Justine, you know you can’t eat the food here? Because it’ll, like, it’s so disgusting, it’ll give you cooties — the double cooties.”

“Oops,” I said, stopping myself midbite.

At that, all the girls giggled.

“Go ahead and eat it,” a second girl said. “As usual, Ann’s being a tad dramatic.”

“You sure?”

“I mean,” she said, “it might not be gourmet, but it won’t make you sick.”

“If you say so,” I said.

Then the first girl, Ann, turned toward me and, with the smile still on her face, said: “What’s that dress you’re wearing? Is that some San Francisco style or something?”

“It’s a paper dress,” I said it. “Vintage.”

“In other words, it’s old, right?”

“From about 1968, 1969.”

“Is that, like, a trend out there?” the other girl said.

“It’s more that I’m personally into the Mod look,” I said, actually relaxing into the conversation as the girls beamed what looked like genuine welcome toward me.

But no sooner had I started to explain the difference between “Mod” specifically and “flower power” or “retro” in general, then the first girl, Ann — the one with the beautiful dark skin and ridiculous cheekbones — said: “And if it gets too hot, you can just rip a couple of holes in it and — voilà — instant air-conditioning!” Everyone cracked up.

My face was on fire all over again, so much so that I could feel the heat flaming out of my head and radiating all around my body. Too bad it didn’t just incinerate me. It was all I could do to mumble a “Yeah, right” without choking on my turkey on whole wheat with lettuce and mayo.

I ran back into the bathroom, slammed the stall door closed, and called Eliza, whose phone, of course, wasn’t on. Then I texted her: “New Jersey bites! I feel like I’m wearing a giant upside-down Dixie Cup!” After I pressed the send button I felt a little better, but not enough to stop me from feeling like the world’s biggest idiot — a girl who wasn’t only plump and pink and a misfit, but someone so desperate that she resorted to wearing clown clothes. After all, my own father barely paid attention to me.

Later, when Mom asked me how my first day of school went, I said what I always said: “Fine.” Then I went upstairs, ripped my dress into shreds, and put them in the trash can. But at least I didn’t cry.

I swear to God, my mother loves the dog more than she loves me. She calls her “darling” and makes up songs about how beautiful she is. Then, right in front of my face, she’ll say: “And unlike some girls, you don’t whine when I won’t buy you hooker shoes, do you, Lucy?”

“Meryl, I’m almost sixteen. And they’re not hooker shoes.”

“You’re nowhere near sixteen,” my mother says, reaching for her ubiquitous can of Diet Coke. “And they are, too.”

She’s a therapist who sees patients, but mainly, she’s made a career out of writing about me. Have you heard of the Daughter Doctor series by Meryl Sanders, PhD — Navigating the Normal: Tears and Tantrums during the Teen Years, or Mothers and Daughters: The Forever Bond? That’s right: They’re both hers. And I’m her star witness, her heroine, her guinea pig and protagonist all wrapped up into one. Someone to be dissected and put back together in the pages of her books. “But no one knows it’s you!” she says when I ask her to write about something else. “Not only do I always use my maiden name, but I never use your name at all. Not to mention that the mother-daughter bond is my expertise, and people deserve good, sound advice. Don’t you agree?”

“No.”

“Honey, I am you,” she says. “I know you better than you know yourself.”

Except she doesn’t, not anymore. Yeah, maybe when I was little, and I could tell her everything, and she always knew what to say and how to make me feel better. But now? Forget it. It would end up in one of her books. Which is why, just to take the most prominent example, she doesn’t know that while I was in Paris last summer, studying art and French at the University of Paris, I dated a twenty-year-old named Arnaud. When I was with him, it was as if my entire body was made out of magic. Like I glowed, and sparkled, and flew over the heads of ordinary people.

In addition to studying philosophy (and writing his thesis on Jacques Lacan), Arnaud is a poet. He even wrote poems about me. I can’t remember how they all went, but here’s a part I do remember: Sa peau soyeuse comme la brume soyeuse/Ses yeux comme le ciel et comme le soleil . . .

Which means: Her silky skin like silky mist/Her eyes like sky and sun . . .

Which sure beats, “My own daughter is a perfect example of a teenager when the unruly passions meet the unruly hormones, and our darling baby girls morph before our eyes into spastic legs, barbed remarks, and budding breasts.” Gee, thanks, Mom. I love to be the butt of everyone’s jokes.

“Ah, New York, city of dreams!” Arnaud said the first time we met, which was when we were standing in line at the ATM just outside my dorm. I was wearing my NYU T-shirt, so I guess he thought I was a student there. “One day I will go to New York,” he said. “Perhaps you can show me around?” I didn’t tell him that I lived in New Jersey with my family and was still in high school, but I figured that it was no big deal — after all, it was just a conversation in an ATM line.

“What are you studying?” he continued in English. “Art? Literature? Dance?”

“Art,” I said, which was at least partially true. I didn’t paint or draw or whatever, but I was taking a class on the early modernists, particularly Picasso. I’d already been to the Picasso Museum twice.

“You stay here?” he said, indicating the dorm I lived in with a nod of his head.

“Malheureusement, oui,” I said. (Which means: Unfortunately, yes.)

“So much better to have a place of your own, non?” he said.

“C’est bon,” — it’s okay — I said.

As far as the dorm went, though, I really didn’t have a choice. It was either live in the dorm, which I knew I was going to hate, or not go to Paris at all; that’s

how against it Meryl had been. All I can say is thank God for my father, because even though there are days when I don’t get to see him all that much (he’s a doctor and sometimes has to work long hours), he’s always, as in always, on my side.

Which is why, in the end, Meryl agreed to let me go to Paris, because Daddo had said that he thought it would be good for me to study abroad, adding that it wouldn’t hurt my college prospects any to improve my French.

So I was all set, and everything was parfait (perfect), except for one detail: I’d forgotten to pack my raincoat! I could have strangled myself, too, because not only did it rain ALL the time, but also, my raincoat wasn’t just any old raincoat: It was this totally awesome Donna Karan that I got for my birthday after I’d begged for it for about a thousand years, and where better to wear something that awesome than Paris? As usual, though, if it hadn’t been for Daddo, I never would have gotten it at all, because Meryl had been against it from the beginning. I know because I overheard them talking one night, with him saying, “But she’ll probably wear it for ten years,” and Meryl saying, “Do you have any idea how much you spoil that girl?” Daddo was just the best, though, and in the end, it had been Meryl who’d given it to me, saying that because I was special, she’d wanted to give me something special. Made of elegantly brushed black sateen, it flared out at the waist and had wide black velvet lapels and cuffs. I’d found it online and was instantaneously obsessed. I’d simply never seen a more beautiful piece of clothing. I was so angry at myself for having forgotten to pack it that I even told my roommate about it. Not that she could care. She studied 24/7 and went to bed by ten. She never said so, but I could tell she was jealous of me. Like when I started seeing Arnaud? All she could say was: “Isn’t he kind of old for you?”

I loved Paris, though. I loved the wide boulevards and the old buildings and the way people stayed out late at night, talking and laughing. I loved being able to take the Metro everywhere and shopping at little outdoor stalls. And most of all I loved the sense that I was on my own, free to be myself without Meryl always watching me and breathing down my neck and checking to make sure I wasn’t developing an eating problem or didn’t have social anxiety disorder or ADHD or wasn’t “experimenting” with drugs or all the other things that she loved — just LOVED — to write about.

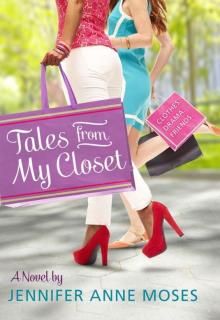

Tales From My Closet

Tales From My Closet