- Home

- Jennifer Anne Moses

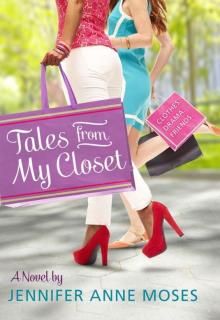

Tales From My Closet

Tales From My Closet Read online

For Rose

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

CHAPTER ONE: My Life on Planet Toilet Paper: Justine: Justine

CHAPTER TWO: The Raincoat: Becka

CHAPTER THREE: My Own Private Pajama Party: Robin

CHAPTER FOUR: Women in White: Polly

CHAPTER FIVE: Blanderella: Anna

CHAPTER SIX: The Day of Dread and Pancakes: Justine

CHAPTER SEVEN: The Promise: Becka

CHAPTER EIGHT: The Flying Dolphin: Polly

CHAPTER NINE: The Return of the Robot: Ann

CHAPTER TEN: What to Wear to Therapy: Robin

CHAPTER ELEVEN: The Great Blue Whale: Polly

CHAPTER TWELVE: The Debate Dress: Ann

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Vacation Humiliation: Becka

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: The Stain: Robin

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Blue Is the Color of My Daddy’s Lies: Justine

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: The Varsity Jacket: Polly

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: The Most Beautiful Boots in the World: Robin

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: Raincoat, Raincoat, Go Away: Becka

CHAPTER NINETEEN: The History of the Red Dress with the White Flowers: Ann

CHAPTER TWENTY: Drama Central: Justine

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: The New Scarf: Becka

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: The Varsity Jacket, Take Two: Polly

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE: My Closet, Myself: Ann

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR: An Original Libby Fine: Robin

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE: Five Groovy Chicks: Justine

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

I hate being the new kid at school. Just. Hate. It.

And I always am. Okay: maybe not always. Maybe not every year. But almost. Or at least it seems that way. First Houston, then Germany, and then Saint Louis, back to Germany, and then, for two whole years, San Francisco, and now I’m in tenth grade and starting all over again, this time in West Falls, New Jersey, which my mother says is, quote, “so sophisticated,” and my father says is, quote, “close to everything.” By which he means: (a) his office and (b) an airport.

“Don’t worry, Pooky,” he emailed to me from his office downtown on the day after he’d broken the news. “They have shopping there, too.”

Ha. Ha.

He gets transferred around a lot. He also travels. The rest of us — which is me, Mom, and our cat, Skizz — follow. Before she’d had me, Mom had been a dancer: She’d been a member of a company in Boston. Now she jokes that she’s his senior staff and I’m his junior staff.

Our New Jersey house, which I’d secretly named Homely Acres, has three levels, connected by half flights of stairs, and a two-car garage. The room my parents chose for me is on the second level, same as theirs, but unlike theirs, mine is painted a pale, sickening lavender-pink and smells vaguely of sugar, like maybe there’s ancient spilled Coke that soaked into the floorboards. There’s no point in getting it repainted, either — not the way we move around. “You’ll love it,” Mom said.

We moved in early August, just in time to arrive in West Falls for my fifteenth birthday, which I celebrated with Mom at a not-very-good Chinese restaurant, because even though he’d promised me that he wouldn’t miss what he called my “big day” for anything, Dad ended up working late, calling me on my cell phone while I was in mid-sesame-noodle-slurp. “I’m so sorry, Pooky,” he said. “I’ll try to make it up to you soon, okay?”

West Falls itself was dead, and that’s because everyone over the age of two and under the age of ninety was at the beach. As for people my age to make friends with? It was as if they’d all been vaporized and sent to another planet.

“Don’t worry,” Mom said. “Once school starts up again, you’ll be back in the swing.”

I hated when she said that: back in the swing. What did that even mean?

In San Francisco I’d fallen in with a bunch of nerdy brainiac types, and through them I met my best friend, Eliza. Mainly we hung out at the beach and, on weekends, explored the Castro or the Haight or any other neighborhood that, once upon a time, had been utterly cool. It was on one of these excursions that I discovered vintage. It was a whole new look for me, a mash-up of hippie and gypsy and blues singer. The look made me feel not just visible, but also like a person in my own right, and not just an extension of my parents’ ideas about who I’m supposed to be.

Neither one of them was exactly crazy about my new look, though. Mom told me straight-out that she thought I looked better in what she calls “normal” clothes. Dad barely noticed at all. Even when it came to my going-away party, he barely glanced up. It was cold and misty, so I wore my absolute favorite dark-green velvet hip-hugging bell-bottoms with black ballerina slippers and a pink silk top, bona fide vintage Pucci.

“Have fun, Pooky,” he said from behind his computer.

I’m Justine. The story they told me was that I was supposed to be Justin, like my grandfather who died before I was born, but then I turned out to be a girl.

Justine Ruth Gandler.

The. Worst. Name. Ever.

Another thing Mom thought was just swell about Homely Acres? It was right across the street from a girl exactly my age and her little brother. Only they were at the beach. “Everyone says they’re very nice,” Mom said. “And there’s another girl who lives just up the street, too, who goes to your high school. She’s supposed to be very nice, too. Everyone said so.”

“What do you mean, everyone? We don’t know anyone here, remember?”

“That’s not exactly true, darling. I talked — at length — to the people we bought this house from. Very nice people. Very nice. They told me that we were in luck because of the nice girls across the street and up the road. I’m sure they can’t wait to meet you.”

“Goody,” I said.

I didn’t know which was worse: August with no one around other than my mother (because Dad was already working 24/7) and nothing to do but lie on my bed in my puke-pink bedroom with Skizz sleeping on my stomach missing Eliza, or starting a new school. Again.

“What are you going to wear?” Eliza wanted to know.

“I’m not sure,” I said, though I’d been obsessing about it for days, trying and rejecting half a dozen different outfits, including movie-starlet-style cutoffs with a white button-down cinch-waist blouse, a vaguely Indian-looking printed silk maxi skirt with ankle boots and a black tank top (it was from the Gap, but it still looked great), and a black classic sixties one-piece mini with a silver zipper up the front, which I usually wore with red cowboy boots.

“You? Not sure? Since when are you not sure?”

“I know. But it’s different here. For one thing, it’s hot.”

“Of course it’s hot. It’s summer.”

“Yeah, but here it’s sticky hot. Humid. Like the air is filled with spit.”

“Gross,” she said. Then: “I’ve got it! What about your leopard-spotted leggings with a big top?”

“You’re not listening!” I said. “It’s hot here! I’d boil to death. I’d turn into a puddle of leopard spots and someone would cut me up and use me as a floor rug.”

“Well,” she said, “at least you haven’t lost your charming personality.”

Precisely two, count them, two days before school started, Mom came barging into my puke-pink room saying: “You’re invited to go across the street.”

“Huh?”

“You heard what I said. I was out front watering the grass” — Mom was always watering the grass — “and I met our across-the-street neighbors. Not all of them, of course. The mother. Very nice. Very. Her name is Meryl. She was walking her dog. They’re just back from the beach. Anyway, she — Meryl, the

mother — said you should come over right now, that her daughter has been moping around ever since they got home from vacation and has been dying to meet you ever since she heard we were moving in.”

“Dying to meet me?”

“She wants to meet you, okay? Which means that you’re going.”

I rolled my eyes in a way that I knew drove my mother stark raving mad.

“I told Meryl that you’d be there in ten minutes.”

“Fine,” I finally said, arching my back in such a way that Skizz had no choice but to jump up off of me the way he does when he knows he has to find another bed.

“Now,” Mom said.

I looked down at myself. Earlier that day, I’d been helping Mom in the garden, and I was still wearing my help-Mom-in-the-garden clothes: a pair of too-big army fatigues with my San Francisco Gay-Straight Youth Alliance T-shirt.

“Like this?” I said, even though Mom never approves of anything I wear.

“Just go,” she said.

“And what if I don’t want to? What if this girl is a total queen of mean? Or a weirdo? Or hates short people?”

“For crying out loud, the two of you will probably be best friends.”

Their house was maybe twice the size of ours, with rosebushes out front and miles of flower gardens along the sides. It looked like the kind of house you see in a magazine: perfect. I’d already caught Mom leaning against the window and staring at it with an expression on her face that looked like a permanent sigh.

“I doubt it,” I said.

“If you don’t move your butt over there, I’ll just have to invite the young lady to come over here.” She looked like she was about to cry.

“Forget it, Mom,” I said. “Nobody does that.”

“Please?” she finally said. “For me?”

Dragging myself across the street, I met my neighbor Becka, who was, and this is the honest truth, absolutely beautiful. Black eyes. Black hair down past her waist. Her figure was perfect — like a model’s. Not one ounce of blubber or extra anything on her, not anywhere. And her skin was tanned. She must have been six inches taller than me. She was wearing a blue sleeveless minidress and, even though it was hot, a pink-and-gray silk scarf with little flecks of green, so light it was as if it was made out of clouds: pink clouds, the kind that come out at sunset. We were standing in the enormous hallway, just inside her front door, surrounded by modern art. I felt like I’d landed inside the glossy scented pages of a high-end magazine.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m . . .” And then, I swear to God, I didn’t know what to say, not with this Becka girl staring down at me with her black-black eyes and perfect straight black hair and golden — as in honey-colored — skin. “Um,” I said.

“Hi, Um,” Becka said.

“No,” I said. “My name’s not ‘Um.’ I was just —”

“Kidding,” she said. Then, when I didn’t say anything, she said: “Cat got your tongue?”

We stood there like that for a little while, under the chandelier, and then she said: “Where are you from?”

“All over.”

“I’ve never heard of Allover. Is it in Europe?”

“What?”

“I went to Paris in July. It was très, très jolie!”

“Huh?”

“To study. I was at the University of Paris. Je l’ai aimé.”

“Nice,” I said.

“No,” she said. “Not Nice. I was in Paris.”

“Huh?”

“Nice. It’s a city in the South of France. But it’s not nearly as jolie as Paris.”

“Oh.” I felt like a moron. Becka was staring at my Gay-Straight Youth Alliance T-shirt as if it were coated in bird doo.

“I’m not gay,” I blurted out.

“Who said you were?”

“Not that I have a problem with gay people.”

“Cool? I guess?”

“Because you were staring at my shirt.”

“I don’t generally notice people’s T-shirts.”

“Oh,” I said. I was getting stupider by the second.

“Are you hungry? Want some juice or something?”

“I’m fine.”

“Do you like New Jersey?”

“We only just got here.”

“Are you going into tenth?” she said.

“Yup.”

“Me, too. But I’m going to try to do eleventh and twelfth together, next year. I already have extra credit, from the summer program I did. In Paris. I only need nine more credits to be able to graduate early.”

“I used to live in Germany,” I blurted out.

“Was it très jolie?”

I just stood there staring at her with my mouth wide open like a dead fish’s, while Becka stood tall and regal and tan and terrifying, smiling down at me with her terrifying black eyes, her left hand playing with her pink-and-gray scarf.

Me, I’m more in the short and not-exactly-thin category. Plus my hair? It’s red, curly, and generally uncooperative, which suits my skin, which is white and freckly. (My mother used to tell me that I looked just like Bette Midler. Thanks, Mom.) My best feature is probably my eyes. I’m not ugly, it’s just that I’ll never be in the first or even the second rank of pretty girls. The best I could ever do was hold my place in the almost-second rank by wearing cool clothes and making sure that I didn’t turn into a giant freckle. Versus girls like Becka, who are born knowing that they’ll always be at the very top of the heap.

Trying not to do something completely and terrifyingly geeky, like drool on myself or trip, I gave her a little wave and, saying, “Well, nice to meet you,” made my way out the door.

When I told Eliza about her, she said, “Yeah, but Becka’s just one kid; they won’t all be like that,” which was freaky, because it was pretty much, word for word, the same thing Mom had said. Versus on the morning of my first day at Western High, when Eliza said (on Skype): “YOU LOOK HOT!” Actually, it was Eliza herself who had suggested the outfit, right down to what color fingernail polish I should wear (a pale aqua blue) and whether or not I should wear matching blue eye shadow. (No. Too much.) The one thing we agreed on, makeup-wise, was lip gloss. My lips look like pale worms without it.

The thing is, when you’re the new kid in school, you have to show up on the first day looking like someone — because if you don’t stake your claim to your youness right off the bat, you’ll not only be a solo-tard for at least several weeks, but also, you’ll be an invisible one. Just another kid wearing a T-shirt and jeans and sandals, going the wrong way in the hallways. I knew I couldn’t compete with Becka, and, like, why would I even try? She and I would never be friends. Even so, meeting Becka had had one positive effect on me: I became more determined than ever not to be one of those kids who fade into the woodwork, just one more Gap-swathed shadow with hair on top and sneakers on the bottom. In short, it was crucial that I establish my own brand. And if the dress I was wearing — as authentic, funky, and utterly original as anything I’d ever owned — didn’t do it, then nothing would.

“Yeah.” I grinned into the computer screen. Good old Eliza: She’d gotten up really early West Coast time to cheer me on. “Thanks to you.”

“Yeah,” she said. “But you’re the one who’s pulling it off.”

Which is not at all what Mom said when, a minute later, I came down to breakfast. She didn’t even smile. Instead, she looked at me, bit her upper lip, and said: “You’re not wearing that, are you?”

I didn’t answer. Instead, I very purposefully, and with as much muscularity as I could muster, rolled my eyes.

Because what I was wearing (thank you, Eliza) could not have been more utterly and astonishingly fabulous. It was: an authentic Scott Paper Caper dress in a black-and-white Mod pattern, cut very simply in the inverted V silhouette and falling to about two inches above my knee. Best yet, it had never been worn before I myself bought it at Treasure Chest Clothing. It was lightweight, it was comfortable, it looked great, and best of all,

it was the real deal. How it had survived since 1960-whatever, I have no clue, but there it was, hanging among other brightly colored Mod dresses at Treasure Chest, and the minute I saw it, I had to have it.

Had. To.

And when I pulled it over my head and saw myself reflected in the store’s old-fashioned standing mirror, I knew that it had been waiting for me all those years, as if, instead of me choosing it, it had chosen me. In it, I not only looked slightly angelic — but in this retro rock-and-roll way, like maybe back in the day I’d dated a rock guitarist — but also astonishingly slim. The white of the white paper set off my reddish hair so that it glowed, and the lightness of the material made me feel that I was incapable of sweating. I figured that even my father, seeing me in it, would have to look up and admire me. Except, of course, that he was out of town on a business trip.

Even so, the dress was a miracle, giving me a deep inner coolosity that I didn’t otherwise have. An alluring but friendly self-confidence. A hip-hop knowingness to my otherwise everyteen stride.

“Let’s go,” Mom said, grabbing her car keys so she could drive me as she does every year on the first day of school. We rode in silence until we were two blocks from school and she said: “You know, my mother had one of those things. It ripped the first time she sat down in it.”

“Uh-huh.”

“You know that those things can catch on fire, right? That’s why they went out of style. Fire hazard. Look it up if you don’t believe me. By the time I was a teenager it was all peasant blouses and platform shoes and blue jeans.”

“Am aware.”

“Have a great first day of school,” Mom said, lunging over to give me a kiss. “You’ll see. It’s going to turn out great.”

Tales From My Closet

Tales From My Closet