- Home

- Jennifer Anne Moses

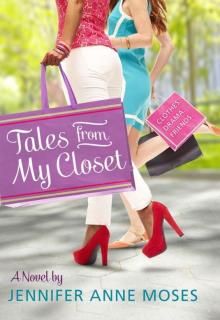

Tales From My Closet Page 4

Tales From My Closet Read online

Page 4

“No,” I said.

“Why on earth not? Don’t you want to meet this girl? From what I hear, the family’s lived all over, even in Europe. She’s probably very interesting, not to mention that she’s exactly your age. Don’t you at least have some curiosity about her?”

“I’m busy,” I said, though I wasn’t. It was more that I just wasn’t in the mood. I’d just gotten an email from Arnaud, and it made me feel farther away from Paris than ever. What was I doing in a place where what passes for sophistication was having your own free-range chickens so you could have free-range eggs and the most exciting thing that ever happened was the annual 10K road race?

Here’s what Arnaud had written to me (in French, of course): “I was walking down the lane where we spotted that elderly man — the one who was singing La Vie en Rose? And I thought: Oh, summer! Oh love! Oh, la rose!”

And I was like: Oh my God. Because of course I remembered that man, and his scratchy-scratchy voice, and the single red rose he wore in the buttonhole of his black jacket, and how Arnaud and I stood watching him, as if joined together in one long sigh. I was just about sick with wanting to be back in Paris with Arnaud when Meryl started calling up the stairs for me to come down right away because “Justine our new neighbor from across the street is here!”

I could have killed her. Instead, I draped my Hermès scarf around my neck and went downstairs.

The girl was just standing there, looking out of place and like she’d never been inside an actual house before, kind of gawking at the art, and wearing the PC tomboy uniform: tight black rainbow T-shirt with “Gay-Straight Youth Alliance” written on it and baggy, badly fitting pants of a style that I can’t even call a style. And her hair: like a halo — no, more like an explosion — of reddish-orange curls. Eyebrows so thick she practically had a unibrow, and hadn’t she ever heard of deodorant? I mean, who was Mother kidding? Does she not know me at all?

The girl stared at my scarf, like she knew. And even though I was angry at Meryl for forcing her on me, for a moment I got this feeling that, in some weird way, at least the girl wasn’t the typical suburban lamiac who can’t think of anything better to do than get her nails done or organize a fun run. Sure, I hated her clothes, but at least she had something original going on, something kind of funky and fun, even if it was hideous. But then an expression like a cow’s came over her face.

“Hi, my name is . . . um . . . er . . . um,” she said.

“Hi, Um,” I said. And, yeah, I know it was a kind of mean thing to say. Okay: It was a horribly mean thing to say. But it just kind of popped out of my mouth, and once it was out, it was out, and I didn’t know how to make it seem like a joke. Plus, there she was, just staring at me, like I was a prized pig, when I hadn’t even invited her over to begin with! Meryl had. Not only that, but I knew from the sweeping sounds that were coming from the kitchen that Meryl was straining her ears to hear every word. As I stood there in the hall, with Meryl probably listening in, and the girl looking at me with her piercing bright-blue eyes, I felt like the world’s biggest spaz.

When the girl finally left, I went back to my room to write back to Arnaud. I told him that I loved the scarf and, once fall came, I’d be wearing his raincoat all the time. (I didn’t tell him that I’d been smelling it, though. I mean, that would have been pathetic!) Then the Little Jerk started drumming, again, and I went down to his room and told him that if he didn’t quiet down I’d personally beat the living crap out of him. Then he went running down the stairs to tattle on me. Next thing I know, Meryl was at my door with a glass of cherry soda, saying that she “wanted to talk.” But I didn’t want to talk. I wanted to get on the next plane to Paris!

Since I was little and playing dress-up with Becka, I’ve wanted to be in the fashion business. Which is why, when Becka’s aunt Libby (who isn’t really her aunt) said I could work for her as an intern over the summer, I almost wet my pants. Which were, by the way, the cutest things ever, even though they weren’t strictly pants, in the usual sense of the word. They were bright blue silky PJ bottoms covered with big pink flowers that I’d bought on sale at Anthropologie, which I wore with a black tank top and belted with a wide bright-pink belt.

What had happened was, at the end of freshman year, I’d kind of run up the charges on my mother’s AmEx card — which she’d said I could use! — shopping online. When she discovered my MISTAKE — which was a MISTAKE and NOT ON PURPOSE, LIKE I TOLD HER A THOUSAND TIMES — first she yelled at me, then she told me that my interest in fashion wasn’t healthy, then she cut off my funds, and then she went out and got me a summer job working at the Temple nursery school, even though I don’t much like kids and never have even though I’ve been babysitting since I was twelve. Anyway, ever since my mother stopped financing my fashion, as in not a penny more, young lady, until you prove to me that I can trust you again, I’d been forced to become more creative when it came to pulling a look together, and because I was growing, I couldn’t simply rely on last year’s fashion crop.

Of course, my mother gave me an incredibly hard time about my new look, but that was nothing compared to the hard time she gave me about my internship.

“You simply have to call Libby Fine back and tell her that you can’t take the internship” is what she told me when I burst into the house with my news. “And the sooner you do so, the easier it will be.”

“No way,” I said. “Forget it. You know how many girls would kill for the chance to intern at Libby Fine?”

“Maybe next year,” Mom said. “That is, if you can demonstrate the maturity to handle something like that.”

“I have plenty of maturity,” I said. “The only person who can’t see it is you.”

“Except that you still owe me four hundred dollars from your last little shopping spree, remember? And now you think it’s a good idea to work around fashion all day long? Think about it: First of all, when it comes to clothes, you have no self-control. Second, I already told Mrs. Shankle that you’ll help out at Temple, and third, fourth, fifth, and sixth, you’d have to get up early in the morning every morning, which you hate, to schlep into the city, where you won’t make a dime, and at the end of the summer you’ll still owe me four hundred dollars, and then you’ll want to buy new clothes for school, and I’ll have to say no, and by the way, you just can’t wear what you’re wearing to school. Or to anywhere. And certainly not into the city every day! You look homeless.”

“For your information,” I said. “This look is totally hot right now. It was in Teen Vogue last month.”

“I don’t care if it was on the front page of the New York Times. You’re not going to take that fashion internship.”

When I refused to back down, Mom turned on the guilt machine, saying that she was worried about me and didn’t want to see me eaten alive in an internship that usually went to college students. She pointed out that both my twin brother and our cousin, John, had lined up paying jobs over the summer. Then she and Dad got into this giant fight, with Dad telling Mom that she was a hover mother, and Mom saying that someone had to be a grown-up, and they went on and on like that for a while until finally my twin brother, Ben, burst into the room in drag. And not just any old drag, either, but my own favorite skirt and blouse, and a blond wig that he’d probably swiped from the drama department at school. Ben liked to “borrow” things.

“Surprise!” he said.

“I need a drink,” Dad said.

“You always need a drink!” Mom said as Dad poured himself a glass of red wine, which is usually what he drinks if he drinks during the day, saying that if everyone in France and Italy can have a glass of wine at lunchtime, then he can, too. “That’s why she’s out of control with my credit cards and with this crazy idea she has about going into the fashion business — not because I’m going overboard, but because you have no self-discipline about anything, obviously. You have no willpower, none at all!” Then she looked at me. “As for you, young lady, you need to exert self-con

trol.”

“I said I’ll pay you back!” I said. “Can’t you just be happy for me for a change?”

“I am happy for you,” she said. “But fashion? What kind of future could you have in fashion? It’s such a grueling world, too. I just don’t understand why you’d rather have an internship than a paid position at the Temple nursery school.”

“Because I don’t much like kids?”

“Oh, and by the way, the Gersons called. They need you to babysit for most of Sunday. I told them you could.”

“What? No way.”

“You need the money.”

“Those kids are brats.”

“I thought you liked them.”

“Last time I babysat them, the little boy put Cheez Whiz in my hair.”

“How are you going to pay me back if you turn down paying jobs?”

So I babysat the Gerson brats, and the little boy kicked his next-oldest sister and then threw a bar of soap at me, and the two little girls didn’t want to do anything but have me play hide-and-seek with them all day, and then Mr. and Mrs. Gerson didn’t get back until almost two hours later than they said they’d be back, and then, as he drove me back home, Mr. Gerson said that he was a little short and would sixty dollars be okay (even though he owed me more like seventy-five), and of course I had to say yes because they were friends of my parents.

“Thanks, Robin,” he said, handing me three twenties, and the next day I went back to Anthropologie and bought a second pair of sleepwear trousers — swishy gray loungers with a pattern of small black butterflies, which, thank the Lord, were on total markdown. I needed something incredibly great to wear on my first day at Libby Fine, and what could be more simultaneously outré and fabulous than wearing PJs and passing them off for cutting-edge? Even if my mother said what I knew she was going to say, which was: “I simply can’t permit you to wear that to the city.”

I swore to myself right then and there that I’d show her — I’d show them all — that I could handle my internship just fine, in my own way, with my own style! Even so, I was kind of nervous walking into Libby Fine my first day wearing loose bell-bottom pajama pants (with a skinny black tank top and a simple gold chain), but Libby was like: “Fashionista!”

Libby had warned me that I’d be doing the grunt work, but it didn’t matter: I totally loved my surroundings — the way the bolts of cloth looked stretched out on the designing tables and how the phones were always ringing with orders or cancellations or some buyer who wanted an appointment to see the new winter line. I didn’t mind running for coffee or taking notes, either, because it meant that I could be part of things a little, listening in at meetings and things like that. A couple of people who worked there said that they didn’t even believe that I was still in high school. They said that I seemed so much older, more mature.

Which is the REVERSE of what I got at home. I’d only been at Libby Fine for one week when, on Saturday afternoon, Dad looked up from the newspaper and said: “There’s an article in here about how hard it is to get into college — the numbers are astonishing.”

“So?”

“So I hope you understand that this fashion thing is just that — fashion.”

“You must really think I’m stupid.”

“No, but I do think that you put frivolity before your schoolwork.”

“Earth to Dad? It’s summer vacation.”

“Is that how you talk to your father?” he said, going red around his temples and eyes.

“What’d I say?”

“My father would have slapped me into Connecticut if I’d used a tone of voice like that.”

“But I didn’t say anything.”

“You’re being fresh.”

“What’s your problem?” I said. A mistake — a big, big mistake, and as soon as I’d said it, I realized that now Dad would get even angrier, even scarier, even more red in the face. I didn’t know whether to fall at his feet and apologize or run for the hills. All I knew was that, once again, I’d crossed over the invisible line that you can’t cross over without getting in a boatload of trouble. I knew he’d never hit me — he never hit anyone — but even now he was pulling himself up from the upholstered chair and crossing the room toward the liquor cabinet, his right hand balled up into a fist and his jaw quivering.

A second later, from the next room, we heard a howl, and my brother stomped in along with our extremely strange cousin, John. John was hopping up and down on the toes of his black-Converse-clad feet. Ben had his head in his hands, saying, “They blew it! They had three men on base and they blew it! What’s the point? I mean, can someone just tell me what the point is?”

Dad and I stared at him. He’d recently grown from being shorter than I am to almost as tall as Dad, and was so skinny that he looked like a stick with a head stuck on top of it. Or like someone had come along when he was sleeping and pulled on either end, stretching him like a piece of gum. Also, he has a huge nose. He went around telling people that the reason he’s so much smarter than I am is that when we were born, I didn’t get enough oxygen.

“Have you started in on any of your summer reading, Ben?” Dad said.

“Yo,” he said. “No worries, Popster. It’s a done deal, yo.”

Which was exactly like Ben, because even though he was a goofball, and had a big mouth, and looked like a giant grasshopper, he was so smart that everyone thought of him as being one of the smartest kids at school, and pretty much always had. He was already writing for the school newspaper, including editorials, which everyone thought was this big, huge deal and an indication that he was slated for greatness.

“How about you, John? Have you done yours yet?”

“Most of it,” John said.

Dad raised an eyebrow.

“That’s more like it,” he said. Meanwhile, Mom must have heard the commotion, because she was walking into the living room, saying: “Are you going somewhere, Robin?”

“Just to meet Polly at Starbucks,” I said. I’ve known Polly almost as long as I’ve known Becka, since second grade. We were Brownies and then Girl Scouts together. But you’d have thought that I’d said I had a date with a terrorist.

“Do you think that’s a good idea?”

“Any reason why it wouldn’t be?”

“Can you afford it?”

“We’re just going to Starbucks.”

“But I thought you and Polly weren’t really friends anymore.”

“Mom? I like Polly, okay? I always have. And just in case you haven’t noticed, Becka’s in Paris.”

“Starbucks is right next to Daphne’s Designer Digs.”

“So?”

“So you have a little shopping problem. And Daphne’s has beautiful things.”

“You’re saying you don’t trust me.”

“I didn’t say that. Did I say that?”

“No,” Ben said.

“Then what did you say?”

When she didn’t answer, I left — but just as the door was shutting behind me, Mom opened it again, and, facing me on our front stoop, said: “You can’t go out like that.”

“Like what?”

“Like that. Like you just got out of bed. You look — I don’t know. Like a drug addict.”

“Maybe I am a drug addict!” I said. “Maybe I’m buying drugs using your credit card!”

There was a pause. Then: “I think you need to talk to someone.”

“What?”

“I think you should see a therapist — someone who you could really talk to. Someone who might be able to help you sort out your problems.”

“Which are . . . ?”

“You have a shopping issue. Don’t wince at me like that. You have a problem, and the sooner you face it the better. This internship thing can only make it worse.”

“Mom! I don’t even spend a lot of money! What am I supposed to wear? Ancient baggy jeans and ugly tops and hideous shoes like yours?”

What was the use? As I turned around and started wa

lking down the driveway, I could hear Dad saying something from inside the house, Mom yelling something back, and the door slamming. Even from halfway up the hill, I could hear the two of them fighting.

But I loved my internship. I hardly ever saw her, but when I did, Libby always said something nice to me or complimented my fashion sense. Everyone else was nice to me, too, saying that I had a good work ethic and a great sense of style. Then Emma Beth came.

Emma Beth, who was already halfway through college, was the real summer intern. The first time we met, she looked me up and down, half smiled, and said: “Interesting choice.”

“What?”

“Your outfit.”

I was wearing, you have to love it, my brother’s extralong blue-and-white-striped cotton pajama top, cinched in with a fat black shiny belt that I’d gotten at Target, so the total effect was of updated shirtwaist dress.

“So you’re the one who got here because you’re related to Libby,” she continued.

“Well, not exactly,” I started to explain, but she cut me off.

“You’re in high school?”

“Yes, but —”

“See you around.”

Emma Beth had a doll’s light-blue eyes and white, petal-shaped face, with hair cut in a forties-style pageboy, and even though she really wasn’t that pretty, she had a certain flair, a certain ultradetached attitude that made you notice her. Her look was strictly office-pro: pencil skirts that hugged her bottom half, and a variety of crisp white shirts, with wedges or high heels and ropes of pearls: classy, well-tailored, feminine, and, obviously, expensive. No castoffs or thrift shops or make-it-yourself for her, and sure, I wouldn’t have minded having a wardrobe filled with several variations of houndstooth skirts and white blouses, but since I couldn’t even afford the knockoff look that you can get at Old Navy, what chance did I have? And she didn’t look like a junior lawyer in her clothes, either, not with the occasional rhinestone poodle jewelry that she wore to add whimsy. Which is how Libby put it, anyway, when she stormed into the design room and announced that, thanks to Emma Beth, she wanted to launch an entire new line, featuring poodles. “Such whimsy!” she said in front of the whole staff, myself and Emma Beth included.

Tales From My Closet

Tales From My Closet